Family and Friends

Robert Allen Zimmerman's family history:

Zigman/Zigmond Zimmerman 1876-1936 Odessa Ukraine, arrived USA 1907. Salesman - shoe store / dry goods.

Anna (Greenstein / Kyrgyz?) Zimmerman 1879 (married Zigmond 1898) Kars Turkey? Odessa Ukraine, arrived USA 1910.

Maurice Zimmerman 1901-1981 Odessa Ukraine, arrived USA 1910.

Marian (Minnie) Zimmerman 1903-1996 Odessa Ukraine, arrived USA 1910.

Paul Zimmerman 1905-1981 Odessa Ukraine arrived USA 1910. Salesman - Woolin Company then shop.

Jack Zimmerman 1909 Odessa Ukraine, arrived USA 1910. Salesman - grocery store.

Abe Zimmerman 1911-1968 born in Minnesota. Oil company (accountant) then shop

Max Zimmerman 1914-1996 born in Minnesota. Newspaper then shop

Beatty (Stone) Zimmerman 1915-2000

_______________________________________________________________________________

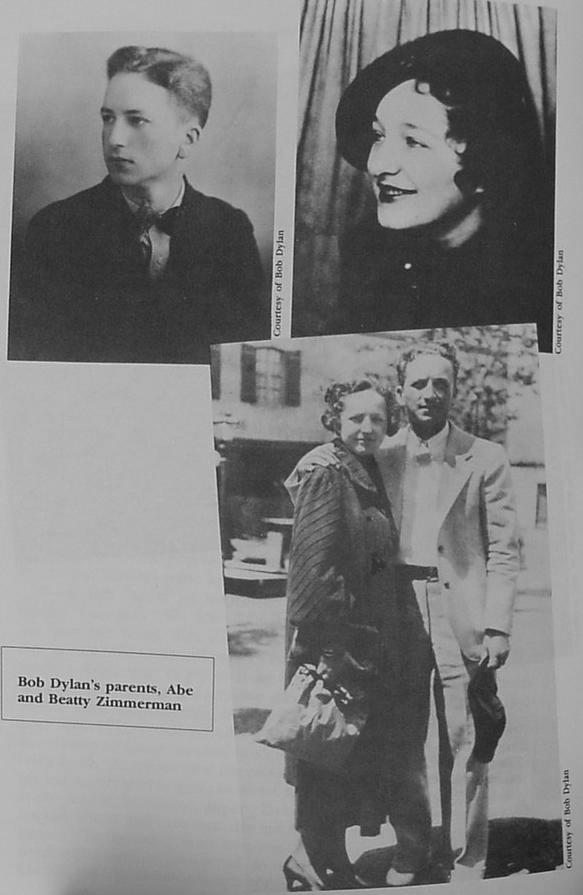

Abram H. Zimmerman, Bob’s father, was born in America, in Duluth, Minnesota, on October 19, 1911, into a family of four other children. If you believe the 1920 census details, Abe was the first of the family born in the USA. It’s more reasonable to believe the 1930 census, which says that Jack/Jake was born in the USA a year ahead of Abe.

Abe’s father—Bob’s paternal grandfather—is Zigman Zimmerman; his Hebrew name is Zisel. ‘I don’t know how they got a German name,’ said Dylan in the 1978 Playboy interview. Zigman was born in the thrusting Russian port of Odessa on Christmas Day 1875, and grew up in an atmosphere of active, vicious anti-Semitism. He seems to have run a shoe-making business before he fled Tsar Nicholas II’s pogroms in 1906. His brother Wolfe not only stayed behind but became a soldier in the Russian army.

Zigman arrived into the US in 1907, through Ellis Island to New York City, like so many others. From there he moved north-west until he arrived in Duluth. He worked as a peddler and sent for his family soon afterwards: by 1910 they had arrived. His wife Anna, formerly Chana Greenstein, born in Odessa on March 16, 1878, had given birth to three children before their emigration: Maurice, aged eight on arrival; Minnie, aged six; and Paul, four. They squeezed into a small apartment at 221/2 West 1st Street, where we presume the fourth child, Jake, was born (though the 1930 census says he was born in Wisconsin). Either way, before the next brother, Max, came along in 1914, the Zimmermans had moved to a house: 221 Lake Avenue North, Duluth. It is the only one of the houses Bob Dylan’s father lived in as a child and as a young adult that does not still exist.

Zigman was still a peddler when Abe was born, but by 1917, Zigman, now styling himself Zigmond H. Zimmerman, was a ‘solicitor’ working for the Prudential Life Insurance Co. He had obtained his naturalisation papers in 1916, but when the USA entered the Great War in 1918, the Zimmermans were forced to register as aliens. His wife Anna told the registrar she was a dressmaker, and that she spoke ‘a little English’. Zigman could speak it but not read it. By 1920 he was a dry goods salesman; later that decade he opened his shoe store but it failed, and by 1930 he was a salesman in someone else’s. All the same, in 1925 they moved again, to a two-storey house at 725 East 3rd Street.

By 1930 the oldest children, Maurice and Minnie had left home, Maurice first working on railway equipment repairs and then as a railway ticket inspector, while Minnie worked as a typist at the Duluth Herald newspaper. Still living at home, 24-year-old Paul had become packer, clerk and then salesman for the Manhattan Woollen Mills. Abe, who by the age of seven had been shining shoes and delivering newspapers, had graduated from the Central High School in 1929, was now 18 and working for the Standard Oil company, first as messenger boy and then as clerk. As Bob commented in 1978: ‘. . . my father never had time to go to college.’ When Abe, aged 22, married 18-year-old Beatty, whom he’d met on one of her weekend trips to Duluth, on June 10, 1934 at her parents’ house in Hibbing, his older brother Paul was best man. They honeymooned in Chicago and then came back to live in Duluth, with Abe’s mother and the three youngest brothers at 402 East 5th Street. Abe’s father, Zigman, had moved out and had an apartment in the Kinsley Apartments on West 1st Street. On July 6, 1936, he died of a heart attack in the street on 2nd Avenue West, in a heat wave, at the age of 60.

Abe duly became a senior manager at Standard Oil, and ran the company union; he and Beatty moved house several more times, finally escaping Abe’s siblings by moving into the upstairs of a duplex at 519 3rd Avenue East, high up on the hillside overlooking the port and Lake Superior. Their first child, Robert Allen Zimmerman, was born at the nearby St. Mary’s Hospital on May 24, 1941, weighing in at 7lb 13oz: ‘about as big as a good-sized lake trout,’ writes Dave Engel, in Just Like Bob Zimmerman’s Blues—Dylan in Minnesota. Robert Allen’s Hebrew name is Shabtai Zisel ben Avraham.

In 1947 the family moved to Hibbing, where Abe’s brothers Maurice and Paul had set up Micka Electric Co. the year Bob was born. Abe became an appliance salesman. When Bob’s little brother David was a bit older, Beatty started working as a clerk at Feldman’s clothing shop in the main street, Howard Street.

Abe contracted polio and suffered its debilitating physical consequences all through Bob’s childhood. ‘My father,’ Dylan told the French paper L’Expresse in 1978, ‘was a very active man, but he was stricken very early by an attack of polio. The illness put an end to all his dreams, I believe. He could hardly walk . . .’ But others reported that he walked with a slight limp, not always noticeable. His mother, Anna, who had also moved to Hibbing, and lived for some years with Bob’s Uncle Maurice, moved into a nursing home in St. Paul and died there of arteriosclerosis on April 20, 1955. She had outlived her husband by almost 20 years.

Her death certificate, with the information supplied by Uncle Maurice, confirmed that she’d been born in Odessa. Dylan contradicts this, writing in Chronicles Volume One of visiting her when she still lived in Duluth: she ‘had only one leg and had been a seamstress. She was a dark lady, smoked a pipe. . . . [Her] voice possessed a haunting accent— face always set in a half-despairing expression. . . . She’d come to America from Odessa. . . . [but] Originally she’d come from Turkey, sailed from Trabzon, a port town, across the Black Sea. . . . Her family was from Kagizman, a town in Turkey near the Armenian border, and the family name had been Kirghiz. My grandfather’s parents had also come from that area. . . . My grandmother’s ancestors had been from Constantinople.’

Abe Zimmerman had a heart attack in summer 1966. On June 5, 1968 he died of a second heart attack. He was buried in Duluth.

Gray, Michael. The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia. New York: Continuum, 2006, 0826469337, page 729f.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

| B.H. and Lybba Edelstein50th wedding anniversary photograph in 1942.

|

| Benjamin David Stone (1882-1945)Bob's grandfather.

|

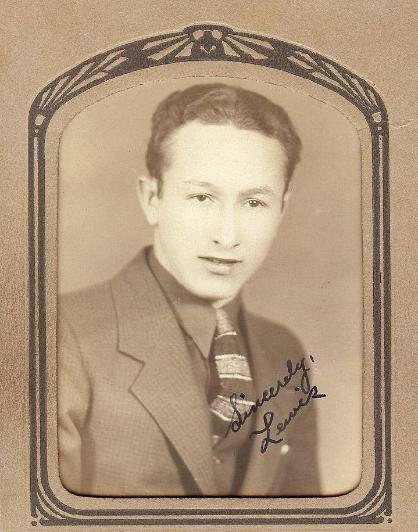

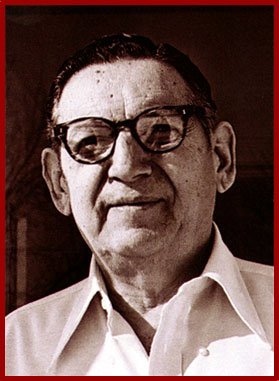

| Lewis Label Stone (1918-2005)Bob's uncle. He owned and operated Stone's Clothing in Hibbing until his retirement in 1967, when he went to work for Mel Sachs at Sachs Brothers Clothing Store.

|

| Ben Stone (centre) had a clothing store in Stevenson Location before the Hibbing store. Ben's brother Ed had a store in Cooley, Minnesota. "Irene Goldfine, Ben Stone’s youngest daughter, was about five years old when this store burned down according to her. Their home was in the back of the same store building which was common in those days."

|

| Paul Zimmerman (21 November 1905 - 17 March 1981)

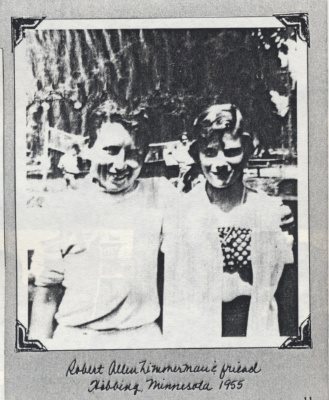

Bob Zimmerman and friend, 1955

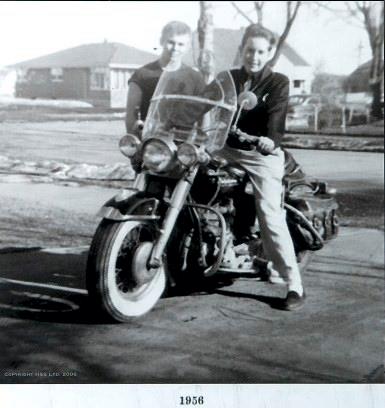

Robert Zimmerman with Dale BoutangDale was "the best rider in Hibbing, a cowboy on wheels and a seasoned weight-lifter". They are pictured here with Boutang's Harley 74, 1956. Photograph taken by Beatty Zimmerman, Bob's mother. (This photograph is seen often on the Internet with the 1956 removed and a modern large 1957 added.) "Waiting in the house was Raatsi on the bed/'I'm gonna pin Boutang's arm,' Melvin, then said/A noise outside! and Raatsi's face had gleam/Ah ha, it was Dale coming on his machine/Raatsi came to the door and opened it wide/Dale Boutang then stepped inside/Roll up that sleeve and let's get to work,'/Said Melvin Raatsi with a great big smirk/'I'm gonna arm-wrestle you to death said Mel the boy/'Shut up,' said Boutang,' I'll take care of you like a little toy..." "We'd pull into the Hibbing Rootbeer stand on Bob's motorcycle when the weather was warm. One time, just outside my house on the old service road, he tried to teach me to ride it. He told me all about the controls, started it up and set me on board. Only trouble was my feet weren't long enough to reach the ground. But I didn't realize that until I'd already taken off. I made about twenty yards in first gear and thought I'd better practice stopping before I went any further, so I tried to put on the brakes; but something went wrong and the engine started revving and I hit a post or a tree and went head over heels. The motorcycle fell over and the rear wheel went crazy with sparks flying and gravel...Bob stood there with his mouth open and his eyes real big, not believing it." -- Echo Helstrom Photograph courtesy of Leroy Hoikkala and Sharon Ness. This photograph was taken by Beatty Zimmerman in 1956 in front of Bob's home. The photograph was a part of Tangled up in Ore a Bob Dylan exhibition at Ironworld. t052008 --- Clint Austin --- austinIRON0522c3.

Bob Zimmerman, Larry Kegan, 1957.

Zimmerman, David [1946 - ] David Benjamin Zimmerman, Bob Dylan’s younger brother, was born in February 1946 in Duluth, Minnesota, two years before the family moved to Hibbing. When David was six and Bob 11, their cousin Harriet Rutstein started to give both boys piano lessons on the Gulbranson upright their parents had bought. Their uncle, Lewis Stone, told Dylan biographer Howard Sounes that David was the better player: ‘David . . . was a very, very smart boy [who] took it all in . . . he could play better than Bob. He was very musically inclined.’ (Six years later, Les Rutstein became general manager of Hibbing radio station WMFG, and got a very hard time about its ‘square’ programming from the less musical Bob.) ‘We were kind of close,’ David told Newsweek. ‘We’re both kind of ambitious. When we set out to do something, we usually get it done,’ to which he added this clipped but truthful insight: ‘He set out to become what he is.’ Toby Thompson interviewed David Zimmerman around five years later. They met in a bar in Minneapolis one weekend in 1968–69: ‘David was short like Bob, but stocky. Close to fat. He wore glasses; and well-tailored sports clothes—stylish— jodhpur boots, mod English jacket, cuff less tapered trousers—the whole trip.’ Zimmerman wouldn’t say much, reacting with frosty silence to Thompson’s prattle, but he couldn’t resist rubbishing the motorcycle crash: ‘Know how Bob hurt himself on that motorcycle? He was riding around the backyard on the grass and slipped. That’s all.’ So he didn’t really break his neck? ‘Sure, if a cracked vertebra is a broken neck.’ Abe Zimmerman told Robert Shelton: ‘When my boys make mistakes, they make big ones.’ David Zimmerman was the culprit who persuaded Dylan that the tapes from the New York Blood on the Tracks sessions of September 1974 weren’t good enough, and to take them up to Minnesota where he gathered together a new group of musicians for Bob to rework them with—overseeing all this because at the time he managed some local groups, was au fait with studio availability and so on. Gray, Michael. The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia. New York: Continuum, 2006, 0826469337, page 728-729.

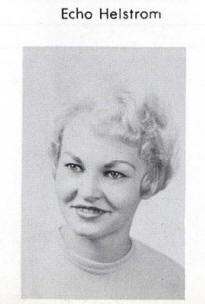

Echo Helstrom" 20 below zero, Let me tell you that your beauty is second to none, Bob" Echo Helstrom´s 1958 Hibbing Highschool Yearbook, Hematite

Echo Star Helstrom met Bob Zimmerman in the 11th grade.She was free-spirited and blonde from a less-affluent section of town than the Zimmerman family and has been frequently cited as the inspiration for the classic folk ballad "Girl from the North Country". In his memoir Chronicles Volume One, Bob Dylan writes "Everyone said she looked like Brigitte Bardot, and she did.", which raises interest because Dylan stated in a 1961 interview "I dedicated my first song to Brigitte Bardot." And at one of his first public performances, in his high school auditorium, he sang a song beginning "I got a girl and her name is Echo..." Also importantly, he recounts in Chronicles: "One of the reasons I’d go [to Helstrom’s house]... was that they had old Jimmie Rodgers records, old 78s in the house." He readily absorbed musical influences and this record collection seems also to have played a part in Bob Dylan’s musical development. "I once wrote a junior high school term paper on music like that. Colored jazz, with a big beat. They wouldn't let me write on rock and roll. That wasn't a fit subject, my music teacher said. Oh, Hibbing is SO hokey." "Bob was a lot luckier with his teachers. He had that nice Mrs. Peterson in music, for one thing, and that made all the difference in the world. The woman I had practically ruined my life. That whole eleventh grade when Bob and I went steady, he had the music teachers snowed. Nobody else could stand how he sung or what he played especially the electric stuff, but people like Mrs. Peterson and Bob's English teacher, Mr. Rolfzen, they had a feeling. Bob would play for anybody, anytime, and I guess that enthusiasm made a difference, too. He was such a sweet convincer." Helstrom, Echo [1942 - ] Marvel Echo Star Helstrom Shivers was born in Duluth, Minnesota, in 1942, by far the youngest child of mechanic, painter and welder Matt Helstrom and his wife Martha. Her brother (also named Matt) was 14 years older than her, and her sister (also named Martha) 15 years older. She was, as she said herself, ‘from the other side of the tracks’ from the middle-class Robert Zimmerman; and this was part of her fascination for him: ‘he was rich folk and we were poor folk,’ as she told Robert Shelton. There was another difference too: ‘he was Jewish and we were German, Swedish, Russian, and Irish, all mixed together.’ In fact, Echo’s mother was born in Ohio and her father in Minnesota, but all four of her grandparents were from Finland. In the 2005 film No Direction Home Dylan says that before Echo there had been another girl, with, for him, an equally resonant name, ‘Gloria Story’; but until he volunteered it, no such name had ever been mentioned in his biography, whereas Echo has long and famously been his ‘Girl of the North Country’. It’s sometimes been guessed— in the dark, either way—that Bonnie Beecher, aka Jahanara Romney, was the ‘real’ girl whose hair ‘rolled and flowed all down her breast’, but Echo has the better claim: she’s the one from Hibbing rather than Minneapolis, and she came first. She had taken accordion lessons, played the harmonium the Helstroms had at home and sang in the school choir. Like Dylan, though, she was into rock’n’roll and like him listened to R&B on the late-night radio station that beamed all the way up from Shreveport, Louisiana. They ‘went steady’ in 1957–58, when they were 16. In the 1958 High School Yearbook Bob wrote against Echo’s name: ‘Let me tell you that your beauty is second to none. Love to the most beautiful girl in school.’ On May 2, 1958, they went to the Junior Prom together, in the school’s Boys Gymnasium, and both danced badly. The Helstrom household was a wooden shack three miles southwest of Hibbing on Highway 73, to which Bob would often hitchhike out after school. Matt Helstrom didn’t approve of his daughter’s young man any more than the Zimmermans approved of Echo, but when he wasn’t around, Bob would play Mr. Helstrom’s three guitars, or listen to his Jimmie Rodgers records, and sing her songs out on their porch. In Chronicles, Dylan describes Echo’s father as ‘The kind of guy that’s always thinking that somebody’s out to take advantage of him’, whereas her mother ‘was the kindest woman—Mother Earth.’ Martha Helstrom (a name Shelton never gives, always calling her, irritatingly, ‘Mrs. Helstrom’) liked Bob, looked on the relationship with equanimity, and felt that Bob ‘seemed much more humble than his family. Both Echo and Bob seemed so sorry for the working people.’ Bob’s brother, David Zimmerman, told Shelton: ‘Bobby always went with the daughters of miners, farmers, and workers. He just found them a lot more interesting.’ In 1968, working as a film-company secretary in Minneapolis to support a child from a failed marriage (cold rain can give you the Shivers), Echo looked back to the events that must have seemed light years ago. Without trying to claim more than her due in Dylan’s story, she told Shelton that they had both felt outsiders together, both misfits in conventional, old-fashioned, narrow-minded Hibbing. ‘We weren’t like the other people at school in any way. I just couldn’t stand being like the other girls. I had to be different.’ Bob was going to be a pop star and Echo was going to be a movie star. Mrs. Helstrom remembered a time when they were going to get married and have a child. ‘They planned to call their child Bob, whether it was a boy or a girl. You know how teenagers are.’ They were drifting apart by mid-1958, with Bob making it ever clearer that he was going with other girls, and they broke up in early summer. She saw him around, but after he left for New York the next time she saw him was at the Hibbing High School Class of ’59 tenth reunion in 1969. Bob and Sara Dylan turned up unexpectedly, and so did Echo. They spoke briefly; Echo was among the old friends who asked for, and received, an autograph. He signed it before he recognised her, then said ‘Hey! It’s you!’ and said to his wife, ‘This is Echo!’, and signed her programme ‘To Echo, Yours Truly, Bob Dylan’. That same year saw the release, on Nashville Skyline, of the rerecorded ‘Girl of the North Country’. They must either have met up or spoken on the phone again, after almost another decade’s gap, some time in the late 1970s: Echo told biographer Howard Sounes that it was 20 years after their schooldays relationship that Bob confessed to her new intimate detail about it. Soon after talking to Shelton in 1968 (for a book that didn’t emerge till 1986) and more than 30 years before talking to Sounes, she had also talked— some might feel excessively—to Toby Thompson, the gawky young author of the first book to explore the subject of Hibbing in relation to Bob Dylan, Positively Main Street: An Unorthodox View of Bob Dylan, published in 1971. He had reached Echo first in October 1968, very soon after Shelton; she was still in her basement apartment in Minneapolis, and gave him the new information that once, when she’d been listening to one of Bob’s Hibbing bands practising, when she’d deciphered his voice from within the over-amplified whole, he ‘was howling over and over again, ‘‘I gotta girl and her name is Echo!’’ making up verses as he went along. I guess that was the first song I’d ever heard him sing that wasn’t written by somebody else. And it was about me!’ It’s always seemed likely that a song from aeons later, ‘Hazel’ on Planet Waves, was also, on one level, about Echo. The album is full of warm memorialising about the Minnesota years—‘the phantoms of my youth’, ‘twilight on the frozen lake’— and to hear ‘Hazel’—‘dirty blonde hair / I wouldn’t be ashamed to be seen with you anywhere’—is to feel a hunch that the song’s tender tale recollects fragments of feeling from the days when Echo and Bob were riding around, coming together from different sides of the tracks, united in wanting to get out of Hibbing—‘you’re going somewhere / And so am I’. Gray, Michael. The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia. New York: Continuum, 2006, 0826469337, page 305-306.

Hohner Echo Harmonica, circa 1959"Hohner Echo Harmonica, circa 1959. Very Good condition. In a custom clamshell case. A harmonica that was owned jointly by Bob Zimmerman and his friend Dale Boutang, played by both during their high school days in Hibbing, Minnesota. Manufactured by M. Hohner, this particular harmonica was chosen because the name of the model was the same as one of Bob's girlfriends in high school, Echo Helstrom. The harmonica has been in the possession of Dale Boutang since their school days together, and Boutang has written a letter attesting to the provenance. "I was a classmate and close, personal friend of Bob Zimmerman, who later changed his name to Bob Dylan. Bob and I shared many of our harmonicas and guitars. This one such harmonica, which I ended up keeping from our high school days. I have had [it] in my possession ever since." Perhaps the greatest testament to ownership of this item is Dale Boutang's crudely scrawled name, along the black edge of the harmonica, between the metal plates." It sold for $6,380.00 (£3,190.00), twice the highest estimate, in 2006. It was later up for sale for $8,500.00 (5,425.00) from Royal Books, Inc., 32 West 25th Street, Baltimore, MD 21218. Dale Boutang was also responsible for selling Bob''s 22-page handwritten high school paper on The Grapes of Wrath that Robert Edward Auctions sold in 2004 (which Bob gave to Dale to help him with his paper). Dale Boutang has had remarkable luck finding things for auction. Do you believe Bob would have owned a harmonica jointly with another boy's name on it? When Dale auctioned his 1959 yearbook with many signatures in it, he did not have anything there from his "close, personal friend" Bob. Both rode motorcycles, so we should see motorcycle parts at auction soon. ;-) Dale a Harley 74, Bob a Harley 45. He moved to Fairbanks Alaska and was an Alaska State trooper, then an investigator for the Federal Government. http://www.robertedwardauctions.com/auction/images_items/item_4874_2.jpg

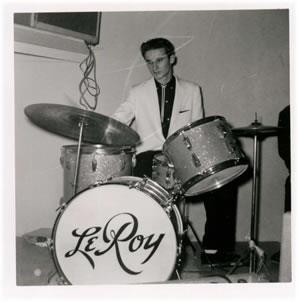

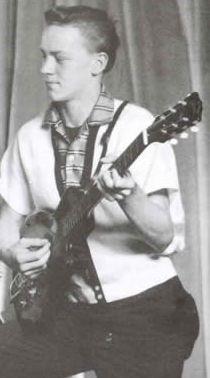

"I knew Bob pretty much from school and everything. Growing up you see each other. It is a small town. You know, everybody knows everybody in town. How we got to meet as far as playing in a band was Monte Edwardson–who is a guitar player; who is very good; he still plays today; he is a natural guitar player–we worked downtown, Monte and myself. Right across the street [from school], we met each other and we walked to a little job, an after-school job. And Bob was just there one day. Monte and I had been messing around with playing drums and guitar; just jamming a little bit. I had taken lessons for quite a few years. So, Bob just happened to say, "Hey, you guys going downtown?" We actually walked from school to downtown, so we told him that we were playing, you know, just getting together and jamming around and playing. So, he said: "Hey, I’m playing piano, mouth-organ, harmonica and guitar. Maybe we could get together and kind of play a little bit." We said, "Yes, sure." So we started playing in Bob’s garage that was attached to his house, that little garage. We jammed in there for quite a bit, and we got a couple of jobs. The first time he ever got paid to do anything was with our band the Golden Chords. Sometimes we’d go into the house to play, because he had a piano in the house. It was just the three of us at that time. Me, Monte Edwardson and Bob. I played drums. We played at the National Guard Armory, a pretty big building. We hired the police department, because you had to have the police, we hired people to collect tickets, we sold tickets, made tickets. We hired someone to clean the place up and everything, and we made money. It was kind of fun. It was one of those things where you put a lot of money out and do something; try to fix a Saturday night rock opera or "jam," and a lot of kids came. That was probably the first time Bob ever was paid to do anything musically. It was a dance. There was a wide-open area, no chairs, nothing, big stage, that’s all. It was a onetime show, that particular one. That was kind of how we got together and started playing. Then we played that talent show, you know, where we actually won but lost, because the kids went crazy [but the judges] gave it to someone else that tap danced. Bob was a little detached on that one saying, "We should have won, you know?" Because, in fact the audience was with us, but they gave it to someone else. We came in second. (He laughs.) That was the three of us as the Golden Chords. The reason we called it the Golden Chords was because Bob was really…he could really chord with the piano and the guitar, really chord beautifully. He was really a natural at chording. And my drums were gold, sparkling gold. So, we said Golden...Chords, that´s how we got the name. Ah, we played some of the Little Richard tunes, [like] "Jenny, Jenny." Some of the southern type music, the blues songs...a lot of Little Richard. Bob loved Little Richard, so we did a lot of Little Richard stuff. It was kind of new for the kids around here. We used to sit together with a reel to reel tape recorder at night and tape the AM-stations that came in really good at night. We taped it so we could listen to the new songs that didn’t come along here. Hibbing was kind of a backward-area. The last to get in. So we listened to the songs from the AM radio, taped them and then Bob would play them, because that was more the type of songs that he liked; the bluesy songs. We listened to Shreveport, there were a bunch of DJs down there that we listened to. Bob was kind of the leader, but he wasn’t really close to anybody. I don’t think he ever had a bestfriend. He was kind of a loner, as we all were kind of loners. We’d hang around the motorcycles, the Harleys, and ride in our convertibles. He had a convertible like mine. When we decide to play we used to go to Collier’s Bar-B-Q. Van Feldt’s owned it. On Sundays they were closed but they still had to clean up the place, do the potatoes for french fries and everything. So we used to go down there–it was right off the main street–and we’d bring our instruments in there, set up where you walk in, and leave the door open. The kids could hear the music from Howard street when we jammed. Bob played guitar and a little harmonica, at that time. What we kids used to do on weekend nights in the summertime was cruise the streets with our cars. That was where the kids used to hear us when they were [cruising or] walking up and down the street. That’s one of the fun things we did together. Bob changed a lot of songs. He listened to a song and he changed them. He didn’t like the way they read. Just like a lot of the songs that he’s recorded. I use to say that he wasn’t copying someone, but he took the basic song and if he didn’t like the lyrics he just changed it to what he wanted. He was a natural. He is a great songwriter. Some songs he didn’t change, others he changed to his own liking. We taped those songs, but I don’t have them anymore. Too bad! You know, Bob was just my friend, and he still is. When he became famous it was like a different person. He has his life and we don’t communicate now. We were friends and we played in the band and all of a sudden he went ...and now he’s a different person. One of the big things that we really enjoyed was James Dean. We went to Steven’s Grocery and Confectionary to look at all the magazines of James Dean; how he got killed in that car accident. We went to movies related to music all the time. James Dean, Brando …things like that. It was usually John Bucklen, Bob and myself. John Bucklen was kind of a beginner. Actually all of us were beginners. But he didn’t play with the band. Bob jammed with a bunch of guys, but that wasn’t [as a] band. Then in the end it broke up. We didn’t really form a band. We played as the Golden Chords here and there and then Bob went to Duluth and got some friends there that played more blues and jazz type of music. Then he took off to Minneapolis.

Monte EdwardsonThe Golden Chords appeared on the 10:00 a.m. Sunday morning "Polka Hour" television show on the nearest TV channel in Duluth in 1958. Monte Edwardson talks about his teenage memories of Bob Dylan in this video.

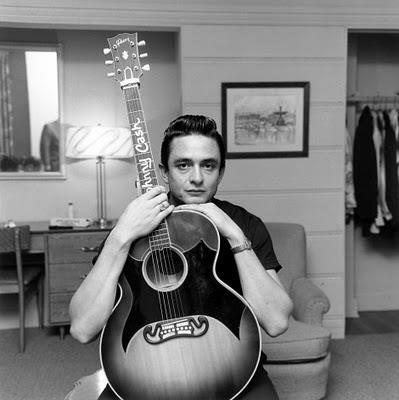

On the tape made with his school friend John Bucklen in 1958 we hear exactly what Bob thought about Johnny Cash then: Bucklen: You think singing is just jumping around and screaming? Dylan: You gotta have some kind of expression. Bucklen: Johnny Cash has got expression. Dylan: There’s no expression! [sings imitation in slow monotone]: ‘I met her at a dance St. Paul Minnesota . . . I walk the line, because you’re mine, because you’re mine . . .’ Bucklen: You’re doing it wrong, you’re just—What’s the best kind of music? Dylan: Rhythm & blues. Bucklen: State your reason in no less than twenty-five minutes! Dylan: Ah, rhythm & blues you see is something that you really can’t quite explain see. When you hear a song rhythm & blues—when you hear it’s a good rhythm & blues song, chills go up your spine . . . Bucklen: Whoa-o-o! Dylan: . . . when you hear a song like that. But when you hear a song like Johnny Cash, whaddaya wanna do? You wanna leave . . .’ By 2004, in Chronicles, Dylan was saying that ‘I Walk the Line’ was ‘a song I’d always considered to be up there at the top, one of the most mysterious and revolutionary of all time’. After his death, Bob Dylan said: ‘Johnny was and is the North Star. You could guide your ship by him—the greatest of the greats then and now.’ The power of television was illustrated in 1993 when a BBC-TV documentary team visited Minnesota and were offered something that not even Robert Shelton’s assiduous and privileged researches had managed to discover—a tape made at Bob’s own boyhood home in 1958 (long before he was Bob Dylan) with one of Shelton’s interviewees, Bob’s ‘best buddy’, John Bucklen. This features Bob Zimmerman the rock’n’roller, playing piano and guitar and singing snatches of five songs (with some shared vocals by Bucklen) interspersed with conversation between the two. The songs are ‘Little Richard’ (composed by Dylan), ‘Buzz Buzz Buzz’ (a hit for the Hollywood Flames in late 1957 to early 1958), ‘Jenny, Jenny’ (a Little Richard song), ‘We Belong Together’ (a minor chart hit in March that year for an adenoidal black harmony duo from the Bronx called Robert & Johnny, i.e. Robert Carr and Johnny Mitchell) and the unknown ‘Betty Lou’ (sometimes listed wrongly as ‘Blue Moon’). Four were first heard, though incompletely, on BBC-TV’s excellent ‘Highway 61 Revisited’, first broadcast in the UK on May 8, 1993. Bucklen, John [1941 - ] John Charles Bucklen was born in Bemidji, Minnesota, on December 20, 1941, but soon afterwards moved the 100 miles or so east to Hibbing. There he became a good friend of Bob’s, the one with whom he made the 1958 tape recording at Dylan’s home featuring fragments of song and of conversation , and the one Dylan phoned up excitedly when he first heard the 78rpm records of Leadbelly he’d been given, to shout down the phone: ‘This is the real thing! You gotta hear this!’ John Bucklen was younger than Bob by eight months and a high-school year below him, but he was, in his own words, ‘a born follower’; Bob also liked the easier atmosphere in the impoverished Bucklen household, with its lesser emphasis on ‘achievement’ and ‘discipline’. John’s father was a disabled miner and a musician, his mother a seamstress, his sister Ruth a lively girl with a record player. Trying out the hipster language they learnt together from James Dean movies and the radio, Bob told John: ‘You are my main man.’ As they grew up, music held them together, and Bucklen, though without his friend’s ambition, nevertheless learnt guitar—playing it alongside Bob’s piano—and before long Bucklen was playing blues on the 1959 Gibson J-50 he still plays regularly today. (Bob played an identical guitar in the late 1960s.) Bob Dylan told Robert Shelton in the 1970s that Bucklen had really been his ‘best buddy’ back in Hibbing, and regretted having been ‘terribly rushed, terribly busy’ when they’d last met. John Bucklen left Hibbing and became a DJ, first in the Twin Cities and then in Fond Du Lac in Wisconsin in the late 1960s. He and his first wife La- Vonne had one child, Chris, now a Minnesota based ambient folk guitarist. John moved on to DJ work in Superior, Wisconsin, in 1971 and then, with second wife Gracie (with whom he has three children), he moved again, though still within Wisconsin, in 1977. He has worked for the same radio station there ever since, claims never to have missed a day of work in 30 years and is, in son Chris’ opinion, ‘an excellent blues musician’. Gray, Michael. The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia. New York: Continuum, 2006, 0826469337, page 103.

Tape of Bob Zimmerman, May 1959Kangas, Ric [1939 - ] Richard Kangas was born in Hibbing, Minnesota, on October 20, 1939. (As he grew up he was known as Dick but today gives his name as Ric.) His mother was a housewife, his father a miner in the Hull Rust iron-ore mines who had previously been a copper and silver miner (and in his youth a lumberjack in the Northern Minnesota Woods). Two years ahead of Bob Zimmerman at Hibbing High School, Ric left in summer 1957, before the two had ever knowingly met. Bob would come to put as his ‘Ambition’ in the 1959 school yearbook ‘To join Little Richard’. Kangas wrote the parallel ‘to be another Elvis’. Like Bob, he too belaboured the gorgeous auditorium of Hibbing High School with early rock’n’roll at a school concert, singing and playing the brand-new ‘All Shook Up’ with a borrowed guitar and amp. Ric and Bob met around town in Hibbing sometime in 1958. ‘I hear you’re a songwriter. So am I,’ Bob said. Ric says the two played together at town hall talent contents and house parties, and auditioned (without success) for the Hibbing Winter Frolic, a big annual pageant, fair and festive event in the town that drew people in from all over the Great North Woods. Their most significant musical collusion occurred in May 1959. Kangas had bought a reel-to-reel tape recorder, and the two of them got together in his bedroom, set it up and recorded four songs. When I Got Troubles, Teen Love Serenade (a short excerpt is featured in the "No Direction Home" film), and two other songs, I Wish I Knew (song by Ric Kangas with Bob backing), and The Frog Song (a song by Bob with Clarence "Frogman" Henry-style vocals). Ric Kangas appears in the film No Direction Home showing us the tape-recorder on which ‘Bob Zimmerman’, wanted to know how he sounded. One track mentioned and excerpted on the film, ‘When I Got Troubles’, is released complete on the Bootleg Series Vol. 7 — No Direction Home: the Soundtrack, and the notes suggest that it is ‘most likely the first original song recorded by Bob Dylan ’— though this cannot be true, granted that the No Direction Home film’s credits claim/confirm that ‘Little Richard’, on the 1958 John Bucklen tape, was also composed by Dylan. Back then, beyond their musical bond was the fact that Kangas had a 1953 Ford (after ‘totalling’ his 1950 Oldsmobile). It’s easy to see why the younger boy would want them to hang out together—and Kangas says they’d cruise around on summer nights drinking gin and orange juice, picking up girls and driving out to necking spots like Snowball Lake; it’s not so clear why Kangas wanted to have Bob in tow. Ric was driving a truck for Kelly Furniture from 1957 till 1960 (a truck that was parked in a warehouse across the alley from the Zimmerman home); for most of that time Bob was still at school. At any rate, Bob would get Ric to drive him around, and one day their destination was local radio station WMFG. It was the start of their destinies dividing. Dylan played some material to DJ Ron Marinelli and was given some airtime on the strength of it; Kangas’ tapes were rejected. They drifted apart when Dylan went off to the University of Minnesota and Ric Kangas got a steady girlfriend out in Eveleth, another taconite mining town some 20 miles away. He’d traded in his Ford for a Harley Davison too, and wouldn’t let anyone else drive that. He says Dylan would sit on the gleaming bike in the Kangas driveway, pretending to be Marlon Brando in The Wild One. Dylan went off to New York City; Kangas got a gig as lead singer for a group from Superior, Wisconsin, the Sonics. This didn’t last, and he was drafted into the US Army, serving from January 18, 1962 till December 17, 1963, stationed in Fort Carson, Colorado. He moved to Tennessee around 1966. About a year later, Kangas moved again, this time to Southern California. He’s since moved around within the Golden State but lives there still. He’s been a Hollywood extra, a stuntman, a magician, a photographer, a portrait sketcher and a wildlife painter. He never quite gives up—even after writing, he says, 900 songs without ever releasing an album. Dryly he calls himself ‘Hibbing’s other songwriter.’ In the late 1990s, Kangas was living in Acton, just south of Lancaster, when he mentioned his 1959 Dylan tape to a banking acquaintance who happened to know Jeff Rosen, who runs Dylan’s office and archive. Rosen phoned, got to hear the tape and eventually brought a film crew out to film a four-hour interview with Ric. About seven years later Rosen called again to say that he and the tape were going to feature in the Martin Scorsese movie, and that one of the songs would be on the soundtrack CD set too. Kangas told the Minnesota newspaper the Ventura County Star that he was paid ‘a guitar, a small royalty cut from the CD and some up-front cash’. He ‘declined to discuss monetary specifics.’ On October 1, 2005, soon after the movie opened, he offered the original reel of tape for auction on eBay (item _7550832002) with an ill-advised reserve 370 price of $1.5 million. The auction ended October 11 with no bids. Quoting Ric’s schooldays ambition ‘to be another Elvis’, the Star reporter notes that in a way he’s made it: these days Ric Kangas is an active performing member of the Professional Elvis Impersonators Association. Kangas remembers another declaration from Hibbing days too: ‘Bob always used to tell us, ‘‘When I make it, I’ll send for you. We’ll all walk down Hollywood Boulevard and we’ll be stars.’’’ Kangas, deadpan, adds: ‘I’m still waiting for that call.’ Gray, Michael. The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia. New York: Continuum, 2006, 0826469337, page 369-370.

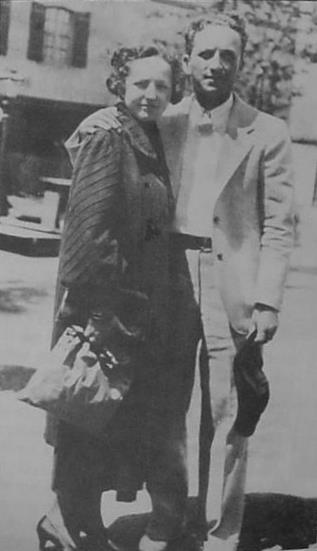

Abe and Beatty ZimmermanBob's father, Abe Zimmerman, was the son of Zigman and Anna Zimmerman, Jewish immigrants from eastern Europe. Zigman was born in 1875 in the Black Sea port of Odessa and grew up in desperate times. As the power of Czar Nicholas II faltered, he blamed Jews for the problems besetting the Russian empire, and thousands were murdered by mobs. Anti-Semitic hysteria reached Odessa in November 1905. Fifty thousand Czarists marched through the streets, screaming "Down with the Jews," and shot, stabbed, and strangled a thousand to death. In the wake of the massacre Bob's paternal grandfather fled the country, telling his wife and children he would send for them when he had found a place to settle. Zigman Zimmerman caught a ship to the United States and found his way to Duluth, one hundred and fifty-one miles north of the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul. Like many émigrés, Zimmerman gravitated to a place similar to the land where he was born. Duluth was a small but bustling port, like Odessa, with an almost Russian climate of short summers and long, bitter winters. Duluth was a fishing port, but its main trade was in the iron ore from the Iron Range, a necklace of mining towns to the northwest. The ore was transported by train to Duluth and transferred to ships that carried it to iron and steel works in Chicago and Pittsburgh. Zimmerman worked as a street peddler, repairing shoes. When he was established he sent for his Russian wife, Anna. She came with three children, Marion, Maurice, and Paul. Three more boys—Jack, Abram (also known as Abe), and Max—were born after the couple was reunited in America. Abe Zimmerman was born in 1911. By the age of seven, he was selling newspapers and shining shoes to help the family. Although Abe was not tall and wore glasses, he was an athletic boy. He was also a musician, and the Zimmerman children formed a little band. "Abe played violin. I played violin [and] Marion played piano," says Abe's brother Jack. "We had pretty good talent and played together at some high schools." Abe graduated high school in 1929, a few months before the Wall Street stock market crash, and went to work for Standard Oil. Bob Dylan's mother, Beatrice Stone—whom everybody called Beatty, pronounced Bee-tee, with emphasis on the second syllable—was from a prominent Jewish family in the Iron Range town of Hibbing. Her maternal grandparents, Benjamin and Lybba Edelstein, were Lithuanian Jews who had arrived in America with their children in 1902, and came to Hibbing two years later. Her grandfather, known as B. H., operated a string of movie theaters. B. H.'s eldest daughter, Florence, who was born in Lithuania, married Ben Stone, also born in Lithuania, and they ran a clothing store in Hibbing, selling to the families of miners, most of whom were also immigrants. Beatty was born in 1915, the second of Ben and Florence's four children. Her siblings were named Vernon, Lewis, and Irene. Like the Zimmermans, the Stones were a musical family and Beatty learned to play the piano. Although Hibbing was the largest of the Iron Range towns, the population was only ten thousand, and the Jewish community was small. "It was quite difficult for us because there weren't too many young Jewish people," says Beatty's aunt, Ethel Crystal, who was like a sister to Beatty because they were close in age. "So we used to go to Duluth to visit our relatives." They were in Duluth, at a New Year's party, when Ethel introduced Beatty to Abe Zimmerman. "He was a doll," says Ethel Crystal. "Everybody liked him." Abe was a quiet, almost withdrawn, young man, and Beatty was vivacity itself, but their differences were complementary. Abe and Beatty married at her mother's home on June 10, 1934, three days after her nineteenth birthday. Abe was twenty-two at the time. The country was still gripped by the Depression. Sharecroppers from the Midwest were migrating to California. Newspapers reported the desperate crimes of gangsters like Bonnie and Clyde, who were involved in a shoot-out in St. Paul in March. John Dillinger was shot dead in Chicago a couple of weeks after Abe and Beatty honeymooned in the city. It was a strange, hard time, and it would be six years before they could afford to start a family. In the meantime, they lived with Abe's mother in Duluth. It took the Second World War, and President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal, to pull America out of the Great Depression. By 1941, Abe had been promoted to management level at Standard Oil, and he and Beatty had enough money to get their own apartment. Beatty was pregnant when they moved to 519 North 3rd Avenue East, a clapboard house with a steeply pitched roof and verandah, built on a hill above Duluth. They rented the two-bedroom top duplex. At five past nine on the evening of May 24, 1941, Beatty gave birth to baby boy at nearby St. Mary's Hospital. He weighed seven pounds and one ounce. Four days later when the child was registered and circumcised he had a name. In fact, he had two. In Hebrew he was called Shabtai Zisel ben Avraham. In the wider world he would be known as Robert Allen Zimmerman. Robert was the most popular name for boys in the country at the time. Almost immediately he was known as Bob, or Bobby. His mother said he was so beautiful he should have been a girl.

1993.35.741.184 Robert Shelton Collection, Experience Music Project permanent collection (Bob Dylan’s American Journey, 1956-1966, 2006) Although Hibbing was the largest of the Iron Range towns, the population was only ten thousand, and the Jewish community was small. "It was quite difficult for us because there weren't too many young Jewish people," says Beatty's aunt, Ethel Crystal, who was like a sister to Beatty because they were close in age. "So we used to go to Duluth to visit our relatives." They were in Duluth, at a New Year's party, when Ethel introduced Beatty to Abe Zimmerman. "He was a doll," says Ethel Crystal. "Everybody liked him." Abe was a quiet, almost withdrawn, young man, and Beatty was vivacity itself, but their differences were complementary. Beatty graduated from Hibbing High School in 1932. This photograph: is left out for two reasons. One it is Duluth, not Hibbing. Two it is not Bob but a niece of Abe's that is said to be the child.

|

| Beatty and Bob Zimmerman, 1945.Now the fifth daughter on the twelfth night Some Sunday Morning, Accentuate The Positive. May 12, 1946 – Mother’s Day Celebration – Duluth, MN He stamped his foot and commanded attention. Bobby said, ‘If everybody in this room will keep quiet, I will sing for my grandmother." June 9, 1946 – Aunt Irene’s Wedding Reception – Covenant Club, Duluth, MN Bob’s first paid performance. An uncle said, proffering a handful of bills, “You’ve got to sing.” He refused. The pleading increased, although the fee remained the same. “So he sang,” his mother said, but not until he had announced: ‘If it’s quiet, I will sing.’” … Everyone was quiet as Bob’s two-song repertoire was repeated. Again the audience cheered, and Bobby walked over to his uncle and took the twenty-five dollars. He approached his mother with his first gate receipts. “Mummy,” he told her, “I’m going to give the money back.” He returned to his uncle and handed him the money. He nearly upstaged the bridal couple.

In May of 1932 Beatrice Stone graduated from Hibbing High School. She was listed as a member of the Darwin Science Club, Volleyball, and Track. Beatty’s disposition was described as being “debonair” and her pet peeve was “The depression on dates”.

Julius Edelstein (1896-1977) in front of the Victory Theater, 1922.Benjamin Harold Edelstein (1870-1961), a salesman from Kovno Lithuania had arrived in Hibbing from Superior, aged thirty-six, with his wife, Lybba (1870-1942), and his then six children in 1906. Once established in Hibbing, 'B.H.' abandoned selling furniture and stoves and entered the entertainment business, purchasing the first of many Edelstein theatres, the Victory. As vaudeville gave way to the flickering of the movie screen, B.H. Edelstein expanded his operations to include the Gopher on Howard, the State, also on Howard, and the Homer on 1st. That a town of just eighteen thousand could support four cinemas in the forties suggests just how central the images conveyed from Hollywood became to postwar middle America. Aaron and Leah Jaffe Benjamin 1870- and Lybba (Jaffe) (1870-1942) Edelstein Vilkomir, Russia arrived USA 1902 Ben and Florence (Edelstein) 1892- Solemovitz / Stone Beatty (Stone) Zimmerman 1915-2000 Robert ('Sabse') -1945 and Bessie Solemovitz Lithuania arrived USA 1898

Dylan’s mother was born Beatrice R. Stone in 1915, and had an older brother, Vernon. Two younger siblings followed, Lewis and Irene. All born in the US, they were the children of Lithuanian Jewish immigrants Benjamin David Solemovitz (born 1883), who changed Solemovitz to Stone, and his wife Florence Sara né Edelstein, herself one of ten children. Florence Sara was the Florence who would become Bob Dylan’s grandmother — she and the other nine Edelstein children were in turn the sons and daughters of Benjamin Harold Edelstein (born 1870) and Lybba né Jaffe, from Korno in Lithuania. (Benjamin Harold’s parents were David and Ida Edelstein; Ida’s parents were Yehada Aren and Rachel né Berkovitz. Lybba Jaffe’s parents were Aaron Jaffe and Fannie.) Benjamin Harold and wife Lybba, plus the first four of their ten children, left their village of Vilkomir, Russia, in 1902, on the ship Tunisia, arriving into the US at Sault St. Marie, Michigan, by way of Liverpool, St. John, New Brunswick and Montréal. They arrived on Christmas Eve 1902 and settled with relatives at Superior, Wisconsin, across Lake Superior from Duluth. The four children who came with them were Bob Dylan’s grandmother-to-be, Florence Sara (born 1892), Goldie and Julius (1896) and Rose (1899). In Superior, Wisconsin, came Samuel (1903) and Jennie (1905). Their father moved to Hibbing in 1904, brought the rest along in the second half of 1905 and in Hibbing they had their last four children, Max (1906), Mike (1908), Ethel (1911) and Sylvia (1912). These siblings all duly became Beatty’s maternal aunts and uncles. Their father, in partnership with one of his immigrant brothers, Julius, starting with tent shows, set up a chain of Iron Range movie theatres. In Hibbing they acquired the Garden Theater in 1925, renamed it the Gopher and sold it to another chain in 1928. In the 1940s they built a new Hibbing movie house, naming it the Lybba after Benjamin Harold’s wife. On Beatty’s father’s side of the family were the Stones, previously known as the Solemovitzes, again a family of Lithuanian Jewish immigrants. Her father Benjamin David Stone was one of four children, his siblings being Rosy, Eddy and Ida, all the children of Robert aka Samuel Solemovitz (aka Solomawitch aka Salamovitz) and Bessie né Kaner. Robert, the son of Abraham and Mary Solemovitz, arrived in Superior from Lithuania in 1888 or 1889, and five years later Bessie and the children arrived. In 1906 Ben’s younger sister Ida was murdered by a Scot named John Young, who had wanted to marry her. Within a year, her mother Bessie had died ‘of a broken heart’. Her husband remarried in 1909, to another immigrant from Russia, May Levinson, who had three children of her own, Roy, Bennie and Sam. That same year—three years after his sister’s murder—Ben, then aged 26, started work in Hibbing. There he met Florence Sara Edelstein; they married in 1911 and set up a store at Stevenson Location, 12 miles west of Hibbing, supplying clothing to iron ore miners’ families; when the mine was used up, they opened their store in downtown Hibbing instead. Florence’s grandparents— Benjamin Harold Edelstein’s parents— were still alive when Florence and Ben’s first three children, were born: Vernon in 1910, Beatty on June 16, 1915 and Lewis in 1918. But Florence’s grandmother, Ida Edelstein, died at 69 in Superior in 1922, the year before Ben and Florence’s youngest child, Irene, arrived. Florence’s grandfather, David Edelstein, died aged 73 in 1924. Beatty married Abe Zimmerman at her mother’s house on June 10, 1934. He was 22; she was six days short of her 19th birthday. Six years and 11 months later, she had her first child, Robert Allen, on May 24, 1941. Her grandmother Lybba died the year after, on September 5, 1942. Five years after Robert came Beatty’s second child, David. Her father, Ben Stone, died in 1952; her grandfather, Benjamin Harold Edelstein, survived till January 24, 1961, dying in the same Duluth hospital Bob had been born in almost 20 years earlier. Beatty’s mother Florence, the grandmother who then lived in the Zimmerman house when Bob and David were growing up — the grandmother much praised in Chronicles Volume One — died in March 1964. Some years after the boys’ father’s death in 1968, Beatty married again, to a Joseph Rutman of St. Paul, Minnesota. Beatty appeared on stage with Bob Dylan, clapping along to the music during the finale of one of the 1975 Rolling Thunder Revue concerts in Toronto, as shown in the photo on page 40 of the booklet inside the 2-CD set Bootleg Series Vol. 5: Bob Dylan Live 1975, The Rolling Thunder Revue, released in 2002. She died in St.Paul, Minnesota, on January 27, 2000. She was 84. She was survived by her younger brother Lewis, Bob Dylan’s uncle, who died at home in Hibbing at the age of 86 on January 24, 2005. Their youngest sister Irene, now Irene Goldfine, is still alive and living in Arizona. Gray, Michael. The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia. New York: Continuum, 2006, 0826469337, page 642.

|

| Chet Crippa entertaining, 1950.

|

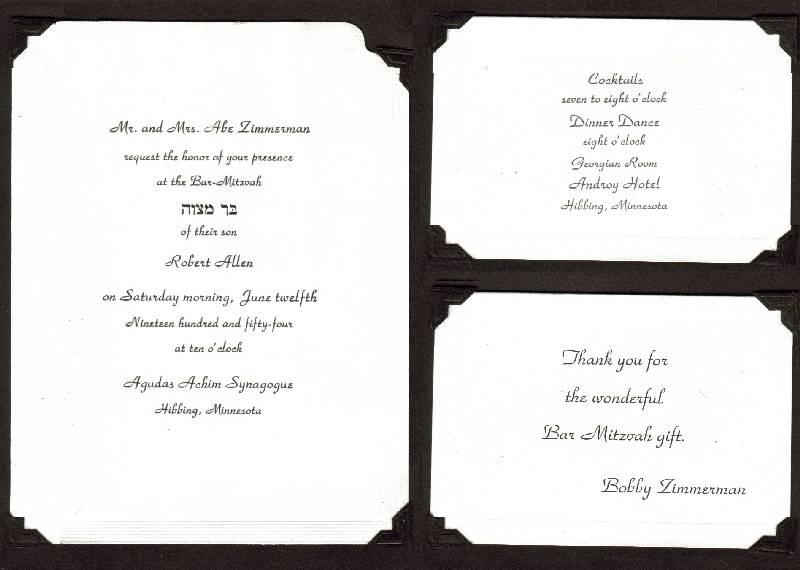

| Bob Zimmerman's Bar Mitzvah (בר מצוה)10:00 Saturday 12 June 1954 20:00 Dinner Dance, Georgian Room, Androy Hotel

|

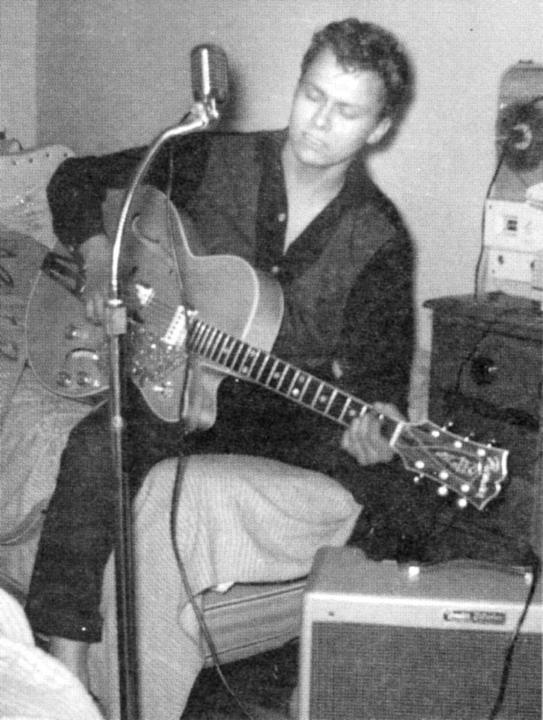

| Dick KangasIn his bedroom "studio" also used by Bob Zimmerman. |